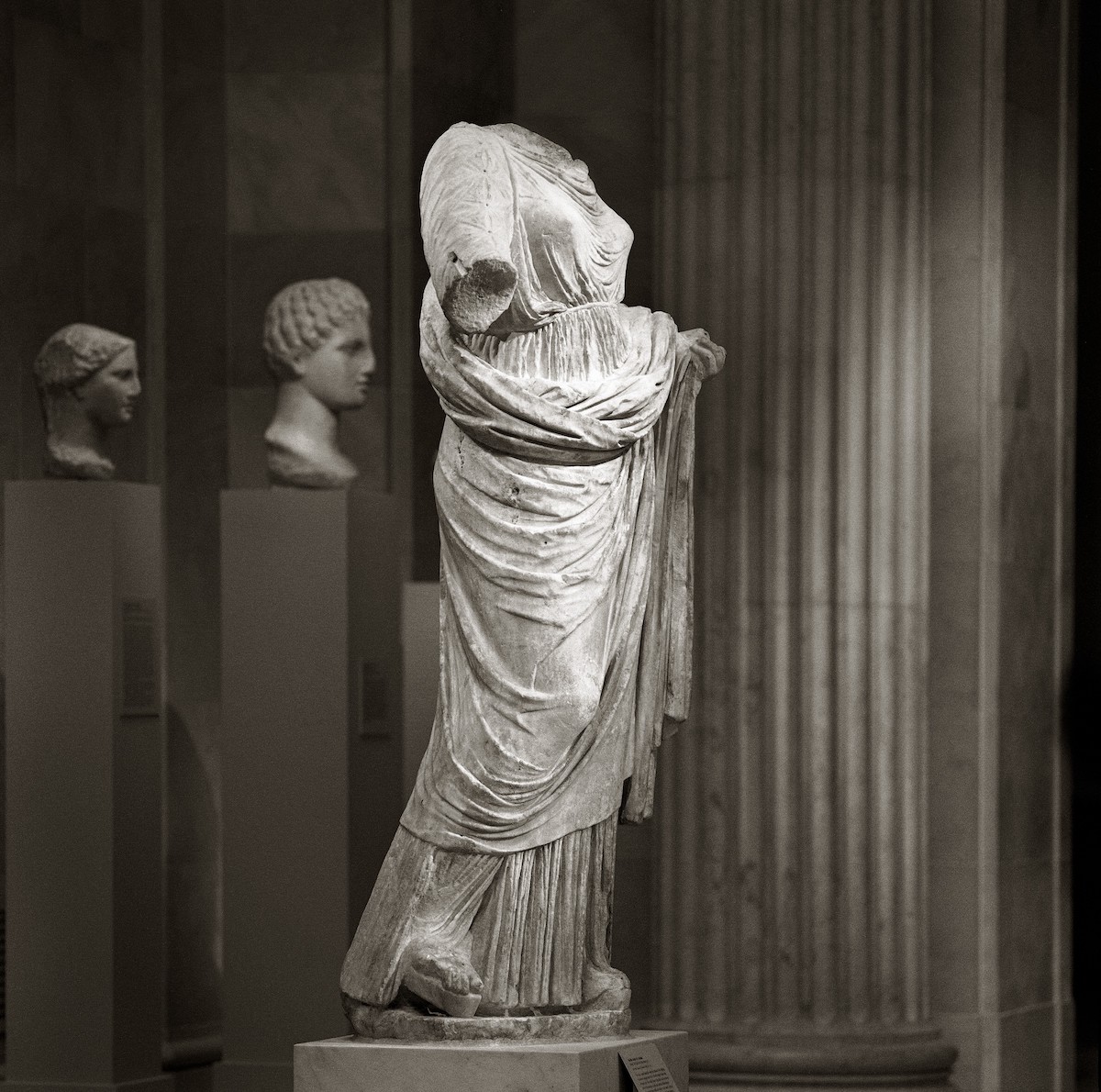

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Frederick F. Thompson, 1903

Drawing from sculpture is a centuries-old learning method for artists. Studies drawn from major works of sculpture offer a direct approach to understanding the power of expression and form. In addition to the technical value of the skills gained through this process, one is exposed to the choices made by the hand of the master. This sort of study has four major aims: to acquaint students with the human body, to educate them on classical structure, to develop their skills in modeling light and shade, and to aid in detachment, which is necessary in the development of objective measuring skills. Beyond helping artists to cultivate basic skills, drawing from sculpture can lead to a defining moment when an artist finds the path to a personal vision. The current masters took their first lessons through studies; they created from the works of earlier masters. One can imagine the rapt attention with which Michelangelo studied the Laocoön, which was dug out of the ground in a Roman vineyard in 1506.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund, 1967

Down through the nineteenth century, copying the antique was considered the best means of teaching beginning students. Classical sculpture offered artists a repertory of poses and forms that could be models of inspiration for their own works. Some artists made it a lifelong practice to copy works they admired. Rubens made himself a large collection of copies of Greco-Roman sculptures, which he used for reference. Many of his studies were assimilated, interpreted, and later incorporated into several of his paintings. The Venetian painter Jacopo Tintoretto, who never sculpted, owned many antique replicas. He spent a considerable sum on collecting casts of ancient and Renaissance marbles. Several of his graphic works attest to his practice of sketching them. And like all the art students of his time, Seurat copied the Parthenon Friezes, the statues of Praxiteles, and Hellenistic sculpture. His study of classical structure and poise gained by this practice influenced his work all throughout his short career.

In 2011, the Metropolitan Museum of Art unveiled a new website that offers access to over 375,000 objects in its collection through a richly-documented online catalogue. High-resolution images of works in the public domain are now available for download. Many museums have since followed suit. This is a great free resource for artists!

To help you get started, I’ve curated some selections from the Met’s collection and grouped them into six categories: animals, clothed figures, group figures, nude figures, portrait busts, and a set I call “in the round.” Click on any of these links, and you’ll find PDF menu of options with each image caption linked to the corresponding catalogue page on the Met’s website. Here, you can look more closely at the piece to decide if you’d like to draw it, then, if so, you can download a high-resolution image file. Also note that for these three-dimensional objects, the catalogue offers images taken from several angles. This allows you to draw and study various positions and gives you a fuller understanding of the three-dimensional experience.

Why do ateliers today continue the tradition of studying the classical antique? The practice helps an artist to develop taste and understanding of aesthetics. Artists never stop drawing from sculpture. It is forever a source of inspiration and resource for study.

If you are interested in feedback on your drawings created from this lesson, please sign up for a private tutorial session.

THANKS COSTA

Thanks so much Costas- miss your class tremendously . I hope all is well- Abigail

Hi Costas, I am all for this! Keep me in the loop please Love Dick

Costa thank you for the introduction to this wondrous Metropolitan Museum website.